Kings, hills and prisons | The story behind Ludgate in the City of London

The history of Ludgate in the City of London… and does a part of the old gate still exist?

An image of Ludgate from a 1680 map after it was rebuilt following the Great Fire

(Wikimedia Commons)

Centuries ago, when London was significantly smaller, the City was enclosed by a wall with several gates providing entrance to the Square Mile. After the population boomed in the Georgian and Victorian era, the capital spilled over the boundaries of the City, spreading east, west, north and south.

The Lud Gate’s Queen Elizabeth statue is now on a Fleet Street church

One of these City gates was Ludgate – or the Lud Gate – situated on Ludgate Hill. The latter was one of three ancient hills in London, the others being Tower Hill and Cornhill. There have been a few theories about the origins of the name Ludgate. The idea that the gate was named after King Lud (who is claimed to have founded London before the Romans arrived) has been widely discounted. Many historians believe the word derives from the Saxon term ‘hlid-geat’, which means swinging gateway into a city. Another popular theory is Ludgate evolved from Flud-gate – a potential barrier to the flood waters of the nearby Rivers Fleet and Thames.

The first Lud Gate was built around 200AD as an entrance into the fortified Roman settlement of Londinium. It was the most western of all the gates into the city. After the Romans abandoned Londinium in the 5th century, the city was largely uninhabited for several centuries. However, it started being used a settlement again around the 8th century as the old Roman walls provided perfect protection from the frequent Viking invasions.

By the 12th century, the area of Lud Gate has become known as Lutgatestrate. Around 1215, the old Lud Gate was repaired or rebuilt when the wealthy rebel barons captured London and strengthened the walls and gates of the city as they battled King John (1166-1216). In 1260, the gate was apparently repaired again under King Henry III’s (1207-1272) reign, with statues of King Lud and other monarchs added to the façade.

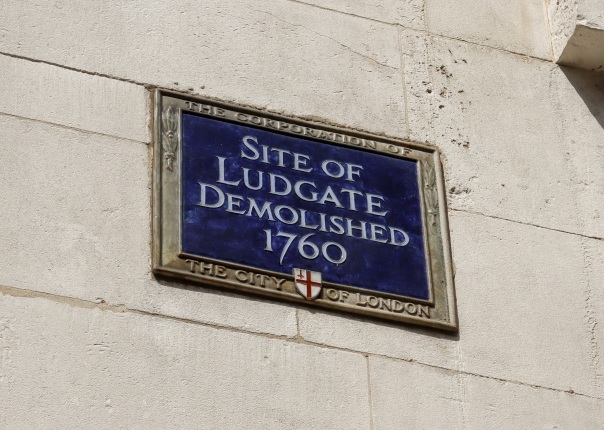

A plaque marking the site of the Lud Gate

By 1359, Ludgate Hill was known as Bowiaresrowe. During the 14th century, the upper rooms of the Lud Gate were being used as a goal for men and women who had committed minor offences. Along with Newgate, Ludgate was one of only two of the city gates being used to incarcerate London criminals. During the early reign of Richard II (1367-1400), Lud Gate gaol became a free debtors’ prison. It was enlarged in 1463 with a tower to increase prisoner capacity while being run by Lady Agnes Foster (d.1484) – the widow of Sir Stephen Foster, former Lord Mayor of London. Lady Agnes abolished the practice of making debtors pay for their own food and lodging.

Is this marker a remnant of the old Ludgate?

While it was a modest prison, there were 30 inmates reported at Lud Gate in 1554. A majority of the prisoners were merchants and tradesmen, who had fallen into debt after misfortune at sea. During Queen Elizabeth I’s (1533-1603) reign, Lud Gate was in a poor state so was demolished and rebuilt in 1586 for £1,500. The eastern side of the gate featured the King Lud statue, while a likeness of the Queen faced west.

The Tudor structure didn’t last long when it was ravaged by the Great Fire of London in 1666. It was rebuilt for the final time as a three-storey gaol and gatehouse, topped by a clock tower. The last Lud Gate didn’t even hit a century old as it was demolished in 1760. The existing prisoners were transferred to Giltspur Street Comptor and the London Workhouse in Bishopsgate Street. The materials were sold for £14, with the statues of King Lud and his sons, along with Elizabeth I, were given to local church, St Dunstan-in-the-West, by Sir Francis Gosling (1719-1768), the then-alderman of the ward of Farringdon. They can still be found there today. The likeness of the Queen stands in a niche over a side door to the church, while Lud and co are in the vestry porch.

The site of the Lud Gate is thought to be where the Guild Church of St Martin within Ludgate and Ye Olde London pub stands. There is a City of London blue plaque commemorating the Lud Gate on the façade of St Martin. There has also been speculation a piece of the old Lud Gate still exists, across the road of Pilgrim Street. As the road bends to the west, there is a rounded piece of stone on the corner of the kerb. Peter Jackson’s 1953 illustrated guide to the capital, ‘London Explorer’ theorised the stone was related to Lud Gate, writing: “This is said to have been one of its cornerstones.”

- Ludgate Hill, City of London, EC4M 7DE. Nearest station: City Thameslink.

A map of Roman London by Walter Thornbury from ‘Old and New London’, 1873.

Image from British Library/Wikimedia Commons.

For more of Metro Girl’s history posts, click here.

Posted on 24 Mar 2020, in Architecture, History, London and tagged City of London, Medieval London, Roman. Bookmark the permalink. Comments Off on Kings, hills and prisons | The story behind Ludgate in the City of London.